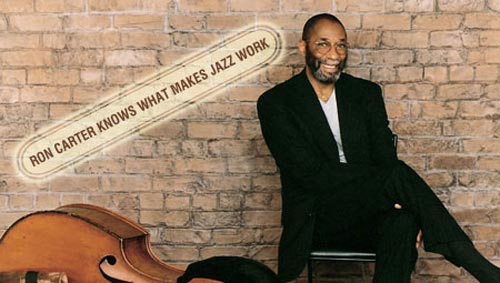

Ron Carter Knows What Makes Jazz Work

Who better to delineate the delicate dance between composition and improvisation than a veteran of approximately 2,000 recording sessions?

“They are fundamentally the same. Jazz composition is the floor that the carpet, which is improvisation, lays on top of, basically,” explains bassist Ron Carter. “It’s hard to say this and not have it sound so simple that anyone can do it because it’s pretty complex.

“What jazz composers bring to the plate that classical composers don’t: They rely on the player of that song to interpret it every night, to bring something new to the plate. Jazz composition is as dependent on the composer’s skill to write a nice piece as it is the performer’s ability to interpret it every night.

“Take Benny Golson’s ‘Stable Mates’: you hear Miles’ version of it, you hear Javon Jackson’s version of it, you hear my version of it. They are all different versions based on the same wonderful melody, and they are all valid.”

But for the typical listener it is the soloist who makes the performance; band members are noticed only in their individual roles as soloists. “Absolutely,” agrees Carter, “especially the rhythm section. They see the guy out front and they’re happy with that. They don’t know what it takes to make that work.”

Carter, who turns 70 next spring, began studying cello as a lad and switched to double bass in his teens. A member of the Eastman School’s orchestra, he graduated with a B.M. in 1959.

Did studying classical cello make him a better jazz bassist? “Probably not. I’m a pretty disciplined person with a focus on what it takes to make things better,” replies Carter. “If I had started out as lamp maker, I would have been just as good a bass player.”

He wasn’t inspired by other bass players but by baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne, who came up when the scene was dominated by Gerry Mulligan and Harry Carney, yet developed a distinctive voice, and trombonist J.J. Johnson, who found a whole series of notes without stretching past the bell of his horn. “J.J. made me aware of all the possibilities on the bass so that I didn’t have to jump up and down like a rabbit,” explains Carter.

Carter moved to New York, joined Chico Hamilton’s quintet and enrolled in the Manhattan School of Music, graduating with an M.M. After Hamilton moved to the West Coast, Carter performed and recorded with Don Ellis, Eric Dolphy, Thelonious Monk, Cannonball Adderley, and Bobby Timmons. He spent only a week in Art Farmer’s group before Miles Davis hired him to join Tony Williams and Herbie Hancock in the rhythm section of his classic quartet.

After that band broke up in the late ’60s, Carter began a career as a freelancer and occasional leader, performing with an encyclopedic list of jazz instrumentalists as well as non-jazz acts as diverse as Aretha Franklin, Laura Nyro and A Tribe Called Quest.

Carter’s next date, after this interview, was a live recording with pianist Steve Kuhn and drummer Al Foster, who was to fly in from Europe the day of their opening at Birdland.

With no rehearsal, how do you make it sound like a working band? “What it takes to sound like a rehearsed band is, in this case, three guys who are aware of each one’s presence and what the music can bring out of each one of them, to make the trio sound like three people playing together rather than three guys that just walked in. As a freelancer, that’s my job, to sound like I belong there.”

Community

Connect with BMI & Professional Songwriters