Exhuming the Blues: ‘Ann Arbor Blues Festival 1969’ 50 Years Later

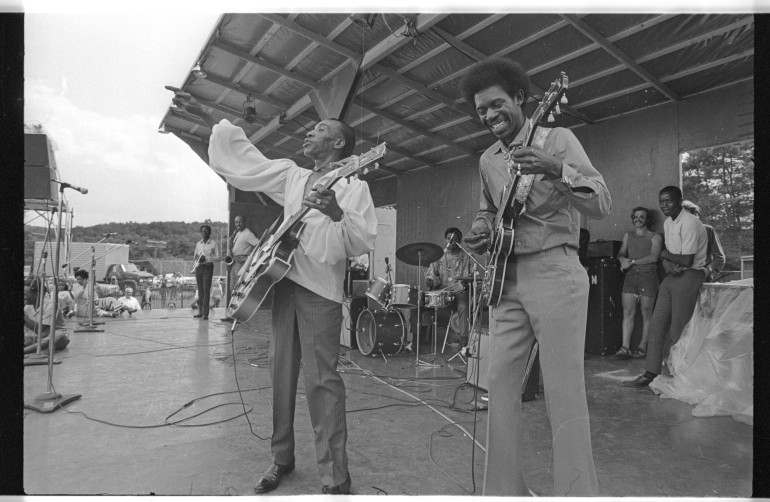

Though not as widely celebrated as other music festivals of its era, the 1969 edition of the Ann Arbor Blues Festival is hailed by many blues purists, acolytes and ardent fans as being just as significant as Woodstock. A seismic gathering of notables from the blues’ past, its then-present and its future – including revered luminaries and BMI songwriters such as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Son House, Magic Sam, Junior Wells, Big Mama Thornton, Clifton Chenier, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Pinetop Perkins, J.B. Hutto & His Hawks, Roosevelt Sykes, Otis Rush and many more – all serendipitously congregated in one place and playing music, turned into a legendary event that was later routinely referred to as “life-changing” by those lucky enough to witness it firsthand.

In the half century since this landmark happening, a tiny fraction of the music captured at the event ever saw the light of day, while a vast trove of recordings lay dormant in a basement. Jim Fishel, a teenaged University of Michigan student and younger brother of festival organizer John Fishel, took it upon himself to record proceedings, albeit never with an idea for capturing music history. The plan was just to have a personal memento of the weekend for him and his friends to enjoy. As the expression goes, little did they know.

It wasn’t until decades later, when Jim Fishel’s son, Parker, happened to unearth those tapes from the family’s basement that the reality of what Jim Fishel had captured sank in. At Parker’s urging, the recordings were exhumed, painstakingly restored and taken to Third Man Records, the label of BMI songwriter Jack White, who helped finally bring Ann Arbor Blues Festival 1969 to full, glorious life in the form of a deluxe, two-volume reissue earlier this year. BMI recently had the opportunity to speak with Jim Fishel about this amazing project, its historical impact and its long journey to fruition. Here is what he had to say.

The story of how you came to document the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in 1969 is pretty remarkable, in that you managed to record this incendiary event almost as sort of an afterthought. Tell us about that and did you have any idea, at the time, that you were capturing something so special?

Well, I was very lucky. In August 1969 I was just an 18-year-old recent high school graduate, but my brother John Fishel happened to be one of the student organizers of the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival. So while I wasn’t directly involved, I had some sense of what was being planned.

As we were leaving Cleveland, my friends and I made a last-minute decision to bring along a portable Norelco tape recorder. It wasn’t thought out or professional. We were just teenage blues fans looking to make a personal memento that we could revisit during quieter times. It certainly never crossed my mind that these recordings would ever be considered blues history!

Once on-site, my brother designated me as a “host” for Arthur Crudup, Mississippi Fred McDowell and Big Mama Thornton. This mostly meant ushering them around the festival site and Ann Arbor and making sure they were well-fed and not lacking in drinks. It also meant the opportunity to spend quality time with three extraordinary people.

Despite these responsibilities (and I hesitate to call them that as they were welcome responsibilities), my friends and I managed to record a majority of the festival while standing, sitting, and carrying equipment – moving liberally from backstage to onstage to the photo pit to the rear of the audience. When the music started, we hit record and hoped for the best…and we got lucky. All things considered, the recordings sounded pretty good, but better yet, the performances were just killer.

I may not have known it when I arrived, but I knew by the end of that weekend that I’d witnessed something special. To see those musicians interacting was something else. After all, it’s not every day you see Arthur Crudup and Junior Wells hanging by a fleet of Cadillacs or Charlie Musselwhite and Roosevelt Sykes embracing backstage. But then that camaraderie backstage spilled over into the performances, leading to a kind of call and response from the stage. Muddy Waters and Magic Sam each paid respects to Roosevelt Sykes during their sets. Mississippi Fred McDowell played “John Henry” at B.B. King’s request. Clifton Chenier shouted out his “soul brother” (and actual second cousin by marriage) Lightnin’ Hopkins. Luther Allison accompanied T-Bone Walker in a meeting of the new and old styles, then T-Bone joined old friend Big Mama Thornton for her set, and Big Mama did her part by bringing out Fred McDowell for a spontaneous performance of “My Heavy Load.” My tapes seemed to capture it all.

Some years after, my brother and I gave Bob Koester permission to release Magic Sam’s breakout set on Delmark Records, which garnered rave reviews. Other than that though, these tapes have remained safely stored and largely unheard for the past 50 years.

As the little brother of John Fishel, the festival’s organizer, were you already versed in the blues?

Well I thought I knew a lot. Like most kids who grew up in the 1960s, I first encountered the blues through folk and rock records and historical reissues. At that time Cleveland also had a vibrant music scene, so I had opportunities to see artists like T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, and B.B. King at Leo’s Casino or the James Cotton Blues Band at a tiny folk and rock club called La Cave. Those live performances only fed my interest in and love of the blues.

As a side note, Cleveland was home to Robert Jr. Lockwood, who had learned guitar at the feet of the legendary Robert Johnson. At the time, Lockwood wasn’t very active musically and was working as a deliveryman for our local pharmacy. One day he was dropping something by our house when he heard some blues in the background, John and I struck up a conversation and subsequently a lifelong friendship. Although Robert didn’t play at the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival, he showed up unannounced at the 1970 festival and John gave him a slot to do a short set. That was maybe the first major gig Robert did as he launched the second act of his career, one that would continue into the 21st century.

Once John got into planning the 1969 festival though, another whole world opened to me. He was not only passing along records and recommendations on new artists, but he was actually going to the clubs and taverns of Chicago to see this music at one of its sources. On a couple occasions I got to tag along and those nights were a revelation. It wasn’t just the music, which was still astonishingly vital, it was the whole blues culture that supported and nourished those musicians and that scene.

Even with those experiences under my belt, the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival showed me just how little I actually knew. In showcasing the diversity of blues music, the organizers made sure there was something new and exciting for even the most die-hard blues fan to discover. For myself and many others, the festival was a crash course in the blues – a dimension that we played off of with the liner notes, musician biographies, and recommended listening that accompany our new release. From the artists that played the festivals to the songs they played, festivalgoers got a real sense of the music: where it’d been, where it was, and where it was going.

Many have compared the impact of the Ann Arbor Blues Festival to that of Woodstock. What was it about this one event that has made such an impression? What are your recollections of that weekend?

Bonnie Raitt (whom I first met at Ann Arbor as a then-unsigned blues artist) called the festival “our blues Woodstock” and there’s definitely something to that. Claims to firsts always come with an asterisk, but to my knowledge nothing with the same focus, concept, and scale had been attempted before. That’s why we make the case for Ann Arbor as the first festival devoted to black blues in the United States and perhaps even in the world, at least in terms of the modern blues festival. No less than Jim O’Neal, cofounder of Living Blues, has written about how “Ann Arbor set both the stage and the standard for all the blues festivals that followed.” Like Woodstock, the Ann Arbor Blues Festival has this enormous legacy. It’s this precious moment where the inventors, innovators, and future legends of the blues could all be brought together and celebrated. And as such, it represents both a culmination of everything that had been percolating in the 1960s and an energizing event that pointed to the future of the music.

But that’s hindsight and the impact of Ann Arbor on most of us who were lucky enough to attend was immediate. In the oral history interviews we’ve done for the project, “life-changing” is the word most used to describe the festival. I certainly agree with that. Despite something like 10,000 people attending over three days, there was a kind of intimacy to the whole affair. It was clear the musicians were soaking up the adulation. But listening back to the tapes, you can also hear them gently guiding the audience, teaching us about the blues. It was not only overwhelming to have set after set of the most amazing blues music, but here was Son House in the flesh telling us about the origins of the blues. It transformed these legendary musicians into real people and fostered a very personal connection. Ann Arbor was never going to be a night at Pepper’s Lounge in the South Side of Chicago, but the musicians did manage to impart of that blues culture to this new audience. And that changed lives.

While I remember many of the performances, the indelible memories are the ones from backstage. Walking into a trailer the first night, B.B. King was holding court, sitting there with his old friend Big Mama Thornton as well as Junior Wells, Mississippi Fred McDowell, and Roosevelt Sykes. Liquor was flowing and they were having an absolute ball. Seemingly out of nowhere, B.B. got out a portable cassette player and played “The Thrill is Gone.” Although the song wouldn’t come out until December, here was B.B. holding an impromptu focus group!

I remember Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf warmly greeting each other on Saturday afternoon. You always think of them in competition, but there they were, sharing a beer against the chain-link fence with Big Joe Williams and Mississippi Fred McDowell, catching up on grandchildren, life on the road, and the recent moon landing. Later on, I looked over to see the Wolf stretched out on the grass taking a quick nap. The rest must have done him good because he made quite the entrance that Saturday night as he rode onto the stage on a borrowed motorbike with his baseball cap turned backwards. One problem with festivals are the tight schedule and short set times, so when the Wolf ran long, Muddy Waters’ headlining set ended up getting cut short. I guess old rivalries die hard.

The genesis of the finished collection is really a family affair, given that it was your son, Parker, who exhumed your tapes from your basement and eventually pushed to have them released. How long did it take to restore all the recordings?

While Parker was in college, he became very involved with WKCR-FM, the world-renowned radio station at Columbia University. WKCR has a storied archive of its own and still maintains a lot of great analog gear. One school break he came home and started going through the tapes in the basement. Stumbling upon my recordings of Ann Arbor, he was taken aback by the names of the musicians on the tape boxes. Starting in 2009, Parker worked with his mentor the Grammy-nominated archivist Ben Young to begin transferring the tapes. It took us a while to identify the performers and the songs, but meanwhile Parker and a team of students at WKCR (including the wonderful Sophie Abramowitz and David Beal who both contributed immensely to this release) began to research the festival and conduct oral history interviews with surviving artists, organizers, and attendees.

We approached Third Man Records in 2012 and they signed on with us for the long haul of clearing performances with artists and their estates, which continued up to the record going to press in mid-2019. To locate blues estates and heirs was a very time-intensive process with lots of twists, turns, and dead-ends. Parker and Ben did the actual restoration of the tapes over a few days in 2012, so the record has been in the can for quite a while. If you compare the Delmark version of “I Feel So Good (I Wanna Boogie) with the newly restored one, you can hear what a terrific job Ben and Parker did.

Do you have any particularly favorite moments on the recording?

I actually recorded over 16 hours of music, so what we selected for this release are all favorites. But there are certainly some performances that stood out for me personally. Howlin’ Wolf delivered a powerhouse set. We selected “Hard Luck,” which just builds and builds with Hubert Sumlin’s blistering guitar breaks. Coming in at over 17 minutes, you get to hear Wolf work the audience and his band as they stretch out in a way you hardly ever get to hear on Wolf’s studio recordings.

It was no surprise that bigger acts like Wolf, B.B. King, and Muddy Waters delivered strong, energetic sets. But there were plenty of new discoveries. Accordionist Clifton Chenier impressed everyone playing his zydeco blues. We included “Tu m’as promis l’amour (You Promised Me Love)” or as he called it, “Ray Charles in French, baby.” Charlie Musselwhite’s fabulous band featured Little Walter’s backing group The Aces as well as Freddie Roulette whose slashing steel guitar was both unusual and made “Movin’ and Groovin’” another highlight.

But perhaps my favorite moment on the record came courtesy of Magic Sam. John had turned me on to his LP West Side Soul, but in Ann Arbor, Magic Sam was a new name to many. This was my first time seeing him live and even with a pick-up band and a borrowed guitar, he managed to bring down the house. Listen to “I Feel So Good (I Wanna Boogie)” and you can completely understand why calls for an encore carried well into the next couple sets. As we mention in the liner notes, one thing was clear: all of that talent in one place brought out the best musical instincts in everyone.

What is it about the blues that makes it so resonant?

That’s the million-dollar question. There’s a quote from one of my favorite musicians (who also appeared at Ann Arbor in 1969), the guitar player Otis Rush: “Nobody can tell you how the blues feels unless they have the blues. We all take it differently.” I think the universality of emotion is what makes the blues so resonant. If you think on it socially or culturally, the Ann Arbor Blues Festival is quite unusual. On the face of it, a young, predominantly white audience relating to these predominantly older, African American musicians and vice versa. They’re each coming from incredibly different backgrounds. But unless you’re really cynical, it works because the blues is this common tongue that unite us all by expressing the joys and pains of the human experience.

Was it Parker who suggested Jack White’s Third Man as the ideal label to put this collection out? What was it like working with them to bring this project to fruition?

Yes, approaching Third Man Records was Parker’s idea. He rightly figured they’d have an interest because of their track record championing American music, especially the blues, and the fact the festival took place in the backyard of their native Detroit. But as we got into it, I think they also took to the fly-on-the-wall quality of my recordings, photos, and ephemera.

We couldn’t have asked for better partners. Despite the size and sophistication of their operation, Third Man has a close family vibe and a DIY spirit that I think fit perfectly with what the Ann Arbor Blues Festival was all about. Jack and label co-founders Ben Blackwell and Ben Swank immediately dug the music, understood the historical significance, and had great ideas about how to present that story. Their whole team is about as smart, creative, and dedicated as it comes. Designer Nathanio Strimpopolus deserves special note as well. He brought the release to life, selecting from hundreds of amazing photographs and all kinds of rare ephemera to craft a beautiful, compelling visual accompaniment to the recordings.

What has the response been like?

The response has been wonderful. In fact, it has been overwhelming. We’ve heard wonderful comments from listeners in places like Japan, France, Australia, the UK, and all across the US. We knew if we could get this project out, people would respond to it and they absolutely have. Not just the die-hard blues fans either. It’s just a wonderful story – these giants of the music once roamed the earth and for three days in 1969, they were all in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Are there any other revelatory recordings still in your basement?

I like to think that there are still some unheard gems left. From 1972-1975, John and I organized the Miami Blues Festivals at the University of Miami in Florida, where I was a student. Though much smaller than what had taken place in Ann Arbor, we were able to host some of the musicians we’d become friendly with at those events. There are some stellar performances from Otis Rush, Koko Taylor, Luther Allison, Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, Hound Dog Taylor, Mance Lipscomb, Robert Pete Williams, Walter Horton, and others.

But there were also some surprises. In 1975, the great bluesman Johnny Shines encouraged us to book former Georgia Sea Islands singer Mable Hillery and even offered to back her up. It’s a wonderful set of classic blues from a virtually unknown singer and a blues legend. After getting the blessing of their estates, Parker and I ended up releasing that set as a limited edition pressing (a small amount are still available), Hotter Than a Polecat Spitting in a Bulldog’s Eye, on our own Americana Music Productions imprint in 2018.

The recordings in my collection capture all kinds of different music though. Ann Arbor set me on a course and I spent nearly 50 years in the music business working with many well-known artists from the worlds of jazz, rock, and folk, among others.

One of the most interesting recordings I’ve got is an audience recording of Max Roach’s set from the historic Newport Rebels counter-festival in 1960. Max had organized the festival with Charles Mingus in protest to the conservatism of the Newport Jazz Festival and his set features long solos from two geniuses who left us too soon: multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy and trumpeter Booker Little. I worked with Max at Columbia Records, so I remember getting it as a gift from him.

But as with Ann Arbor Blues Festival 1969, any potential release of these tapes would require a partner to understand both the importance (culturally, historically, and musically) of the recording and the importance of making sure that all rights holders, including performers and songwriters, are fairly compensated.

Community

Connect with BMI & Professional Songwriters