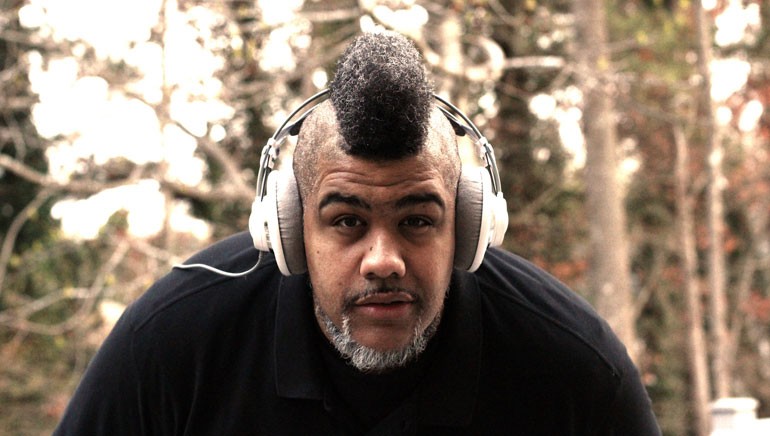

GRAMMY-Nominated Oak Felder Gets and Gives Advice

The writer of Usher’s “Good Kisser” talks music, love, and chart busters

When he moved to the U.S. from Istanbul, Turkey, in 2001, writer-producer Warren “Oak” Felder had a degree in network technologies and artificial intelligence from Istanbul Technical University, and zero music expertise save for his abiding love for rock bands including Rage Against the Machine and Modest Mouse. Felder hadn’t even heard much hip-hop, R&B or soul when he came to Atlanta on scholarship at Georgia Tech, which makes it doubly impressive that in just a few short years, he’s become a GRAMMY-nominated hit maker and one of the most sought-after producers in contemporary music.

Not long after picking up the essentials of beat-making from an uncle, he landed a meeting with L.A. Reid; Felder seized the moment and never looked back, first landing a credit on Chris Brown’s debut. After partnering with Andrew “Pop” Wansel, Felder literally found his groove, shooting to the top of the charts with “Your Love” for Nicki Minaj, which peaked at No. 1 on the U.S. Rap Songs Chart for eight weeks going platinum. A steady flow of major placements followed, including two songs on Alicia Keys’ GRAMMY-winning Girl on Fire; Usher’s “Good Kisser,’ which earned a Best R&B Song GRAMMY nom, and many more for artists including Ariana Grande, Britney Spears, Miguel and Kelly Clarkson, to name just a few. Named a top producer by BMI in 2012 and 2103, Felder won the 2017 BMI Pop Award for co-writing Alessia Cara’s “Here,” which, along with “Scars to Your Beautiful,” gave Felder two back-to-back No. 1 Billboard Top 40 victories. Having set the standard for successful career changes, Felder is now mastering a new skill: shaping the next generation. Unsurprisingly, he’s winning at that too: “Sorry Not Sorry,” the Demi Lovato track Felder co-wrote with production protégés Trevor Brown and Zaire Koalo also known as The Orphanage, went to No. 1 on the Pop charts.

BMI caught up with Felder, a devoted husband and father of two, to talk about the value of being an outsider, the writing process and the studio moment that changed his life forever.

You grew up in Istanbul. How do you think coming to the U.S. impacted the way you write or produce music? What influences from there come across in your music?

My dad is from the U.S. and my mom is Turkish. My parents separated and I ended up being raised in Istanbul. I can speak specifically to one thing that I worked on: I did four songs on Mayer Hawthorne’s Where Does This Door Go, and a lot of the instrumentation from the songs on that album were actually Turkish instruments. One song in particular, “Crime” by Kendrick Lamar, featured a saz (a Turkish string instrument). I think my perspective on Western music was very much as an outsider when I moved to the States. I grew up listening to rock but there was so much music that I hadn’t been exposed to. Even today as a producer, I’m looking at it from the outside. As in what elements I love and what could I do to make it better – a very third-party approach.

I’ve read that you didn’t hear much hip-hop and R&B growing up. Tell us what was it like when you first heard that music, and what about it appealed to you?

Rage Against the Machine had a very good song in the ‘90s, called “Killing In The Name.” There’s a part of this song where the guitar and bass are doing this funky riff. When I heard that, it was like having this thing go off in me like, ‘This feels good.’ In retrospect, I look back at it and I know that there was a part of me that liked the rhythmic side of music. I had heard rap records growing up, but I didn’t really have a lot of direct interest in them. I didn’t hear it in a lot of places, so I had to go looking for it. When I was in the States, I heard it on the radio and TV and I realized that one rhythmic part of the Rage Against the Machine song appealed to me for the same reason that rap and R&B and soul appealed to me. There’s a part of me – and I don’t want to make it sound like a racial thing – but there’s a part of me, being a black man, that makes me really connect to things that have a lot of rhythm and a lot of soul. Not to say you have to be a black man to appreciate those things, I think that it’s good that it can be appreciated universally. Otherwise, my job wouldn’t be as amazing as it is. But there’s a part of me that says, ‘Oh, that’s why I like that part of that song so much’ because the rhythm is so infectious. It’s like seeing in color for the first time almost.

Some of your biggest hits are with amazing women including Alicia Keys, Demi Lovato and Alessia Cara, who’ve bared their souls in anthems like “Scars to Your Beautiful.” Has being a champion of female writers and producers been a conscious effort on your part? How and why did female empowerment become important to you?

Let me preface by saying this. l think that the female perspective is the one that is less perceived. I don’t necessarily think that’s right. I think that it’s easy to assume what women’s perspectives are and how they are going to feel. Especially back in the day, men had terrible perspectives about women. Men had a terrible habit of writing off women. How many times have you heard, ‘Oh man, you acting like a girl?’ The truth is that women have a very interesting viewpoint that is not given enough attention, in my opinion. I’m a very happily married man. There’s nothing that happens in my life that I don’t get without getting my wife’s perspective on it. I think that in shining a spotlight on women’s perspectives you engage the whole world. There was a real chauvinistic thing we used to say in the urban community back in the early 2000s: We used to say ‘If there’s a female artist saying something, women will listen to what she’s saying. Men will listen because they want to listen to what the girls are listening to.’ The reasoning behind it is a little skewed, but I think that the basic concept is that a woman’s perspective tends to have a little more universal perspective. Not that men don’t have something to offer. But we’ve been offering what we have to offer for the longest time. I think it’s important to understand a woman’s perspective. I tend to find it very, very interesting. One of the rules that I have for working is to work on things that I find interesting. Do I want to hear a male get on the mic and talk about how much bread he has or about how many cars he bought or how many times he [had sex with] this chick? Or am I more interested in hearing Alessia Cara talk about how she wasn’t into being at that party, or in hearing her talk about how it feels to grow up in a situation she’s not familiar with? She has a record out now called “Growing Pains” that talks about that. I find that perspective a little more interesting and creative and one that I’m always going to gravitate toward. I think that naturally enables me to gravitate towards female artists.

You’re very versatile and hard to pin down style-wise. How do you define your sound and if you had to pick one favorite song of yours, which one would it be and why?

I don’t have a specific genre that I could describe myself as. If I had to describe my style as anything specifically, I’d say my job as a producer is to reflect the artist. That’s my job. My job as a producer is not to front or stunt on people. There are some producers that do. I see it as being a service industry and my job is to reflect the artists, not myself. They say that producers have big egos and I think that’s true, But I think the best producers are the ones who know how to get the hell out of the way. As far as what my favorite songs are? I always say that my favorite song that I ever produced is the song “Where’s the Fun in Forever?” by Miguel. That song came about from a conversation when I was sitting around with Miguel, Alicia Keys, John Legend and Rodney Jerkins. We were talking about what our biggest fears were. We went around the room and it gets around to me and I said, ‘My biggest fear is death. The idea of not existing.’ Miguel looked at me and said, ‘If you live forever where would be the urgency of life? Where would be the rush to do something meaningful? Where would be the angst in life? Your life would be so listless, boring, and slow if we’re going to live forever. There’s no fun in forever.” The next day he came up to me with the song and said, ‘Let’s record it right now.’ We were in Jamaica doing a camp for Alicia Keys. That song was initially for her, but she decided he probably would be a better fit for it.

Technology, computer design and artificial intelligence captured your attention before music. How are those worlds similar, and how does that knowledge factor into your music making?

I think that every skill that you have as a producer just makes it easier for the idea in your head to become a real idea. Knowing the technology is one more step in making that happen and a lot easier. I think that on a creative level, technology and music are very much siblings. Music is the older sibling of technology, but music is innovative and creative. It attracts intelligent people. Technology is also creative, innovative and attracts intelligent and creative people. But right now, unfortunately, technology and music are having a little bit of a spat with each other. This is because of the positioning of where music is now and how it relates to technology. Tech companies are not necessarily paying what’s due for songwriters. I think it’s something that’s going to get ironed out, but they are a little at odds on a corporate level or on an industry level. That’s sad to me because I feel that they’re two sides of the same coin.

A lot of your process entails spending time with an artist and getting essential truths about them just by talking, eating and having an exchange. How’d that become so integral to your songwriting and creativity, and why is it important?

When an artist comes to me and we write a song and they walk out of the room, they live with that song for the rest of their careers. I don’t. I don’t have to listen to it again, I don’t have play it anymore. But if it’s the artist and it’s their single, Alessia is going to have to perform it for the rest of her life. You have to make sure that what you put down is an indication of what’s in the artists’ head. You almost have to be a psychologist. You have to be able to sit down and put them on the shrinks’ couch and say, ‘Tell me your thoughts and fears. Tell me what you’re dealing with.’ It has to be a natural process. I have seen producers do it in such a clunky way where they say like, ‘Ok, tell me what’s going on with you and your boyfriend.’ That’s so not natural. You have to do it as naturally as possible. As a result of that, I’ve ended up forming a lot of friendships with a lot of artists because we end up getting to a point where they are used to talking to me about issues they might be having. I’ve ended up becoming their pseudo-therapist. I don’t know how many times I’ve gotten a text message or phone call about what to do with their boyfriend or what to do about their girlfriend. I end up becoming everybody’s big brother. It’s a great by-product of the work. You have to get inside their heads so that they want to perform the song for the rest of their careers.

What moment in the studio working with an artist stands out the most to you and why?

I was working with Raven-Symoné. It was one of my first big deal sessions back in 2006 or the beginning of 2007. She came to the studio with her best friend and we hung out for the first day or two talking about different ideas and different songs. We talked about something difficult that Raven was going through. It was a tender subject for her, although she didn’t let on in the beginning of telling us about it. We ended up writing a song called “Love Me or Leave Me.” While she was recording the song, she started crying. I thought it was a beautiful moment because, it was like, ‘Wow, this was a real emotion that’s being poured in the song and that’s great because we want people to feel that. As she felt this emotion, her friend, who she bought with her, was in the booth. When they came out, I ended up talking to her friend. Then, you know, we ended up connecting because of the situation and how emotional it was. We ended up getting to know each other really well. That girl and I, to this day, are still married. That moment stood out to me. It was a very special moment, I think that the emotion and the vibe that the artist had in the room inspired my relationship with my now wife. It’s a testament about how music can affect a person’s life long-term.

You talk a lot about what you picked up along the way from people who’ve shaped you, including your producer uncle, and then that first big meeting with L.A. Reid. By the same turn, you’re passionate about mentoring the next wave particularly through The Orphanage. Why is that important to you and what advice do you give aspiring songwriters and producers?

Once, with Marsha Ambrosius, we were at a show backstage with Quincy Jones. This was early in my career. We were discussing music theory and writing songs. The question was asked, ‘What is the most important element of writing a song?’ Quincy goes around the room and I think everybody pretty much agreed that it’s relatability. Everybody has to be able to relate to the song that’s being written. Then he says, ‘Ok, let me ask you a question: What was the biggest song written in the last 50 years?’ Now listen, it’s Quincy Jones. I’m thinking “Thriller” by Michael Jackson because that’s the only thing you can name. ‘That’s right,’ Quincy said. Then he says, ‘Now let me ask a question. Which one of y’all have ever had a Thriller night? Think about what that song is about. That song is about getting chased by ghouls and zombies and demons. I hope to God nobody can relate to that.” Then he asked, ‘What’s the most important piece of that song?’ “Cause this Is Thriller night,” the first part of the chorus. What’s the next lyric?’ Nobody could remember it but everybody remembered the melody. Then he said, “The first thing you listen to on the song will be always the melody. Your first listen will get you through the door. Melody is more important structurally to any song than anything. And people still don’t know the lyrics to that song.” The thing about Quincy is that he is sort of a natural teacher. I want to say that I picked up habits that like from people like him. I tell you why. Mentoring is a symbiotic process. I mentored Pop Wansel for a long time before he became my partner. He learned a lot from me when it came to the actual craft of producing. I learned a lot from him, too. Sampling, for instance. I didn’t do that often before I met him. Or even the just the essence of creating hip-hop. I learned a lot from him in that regard, and I was mentoring him! I feel that the best protégées are the ones you learn from. I’m applying that now to all the other guys that I’m mentoring with The Orphanage and other producers that I’ve signed. There are so many things that they show me and I go, ‘Wow, that’s cool, I’m going to try to incorporate that.’ I think that a good mentor knows when to put his ego aside and say, ‘There’s something that I can learn from them, too.’ That’s why the process is so important. That’s what gives a producer longevity. If you’re stuck doing the same stuff you did in 2007, guess what? You’ll be doing exactly what those old producers in 2007 were doing, right now. It’s the one reason why I feel like I’ve been able to do this for as long as I’ve been doing it.

What are you most excited about doing next?

I got a whole lot of stuff coming up. I’m really excited about Kehlani. I think R&B is poised to get back to being the next pop culture driver. At one point it was EDM, right now it’s hip-hop. In two to three years it will be R&B. I think that the R&B artists now who are really prominent will be superstars of that time… your Kehlanis, SZAs, your Khalids, like him being Michael Jackson-prominent, and other R&B artists that are coming up. during that period. I’m very, very, very excited about Kehlani. I’m excited about H.E.R. I’m jumping back in with Demi Lovato, There’s Nick Jonas. I’ve been working with him quite a bit. I got a million things going on. I like music in general. I love working.

What made you join BMI? How does the relationship with BMI continue supporting your career and accomplishments including collaborations, the BMI Aspen Song Camp and the SHOF/USC 2017 songwriter/producer panel?

I joined BMI back before I was an actual working producer. I was just doing random beats for a rap group. I wasn’t really focused on being a producer. They mentioned to me you got to get hooked up with BMI or ASCAP so you can get your royalties collected. They gave me the BMI paperwork and I sent in it. From that point on, I was a member of BMI. I met Catherine Brewton, Barbara Cane and the cool people that worked there. One thing that struck me about the people at BMI is how much they cared about the music. More so than some of the people I saw at publishing companies or labels. These people were very passionate about the music itself. I remember in particular, meeting with a great friend of mine, Wardell Malloy. We sat down and had lunch one day. We had a four-hour conversation about music and where we thought it should be going. He and I were so like-minded. That gave me a really good feeling about staying with them.

Community

Connect with BMI & Professional Songwriters